Understanding PFAS, the "Forever Chemicals"

- Environmental Health Project

- Sep 18, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 16, 2023

Every day, nearly every American is exposed to a select group of toxic substances that has been linked to a wide variety of health conditions like cancers, endocrine disruption, and increased susceptibility to infectious diseases like COVID-19.

But what are PFAS and where are they found? How do these toxic chemicals affect your health and what can you do to protect yourself?

What are PFAS?

“PFAS” is an acronym for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. This class of approximately 4,700 substances consists of toxic, human-made chemicals that are used in many industries around the world, and have been used in the United States specifically since the 1940s.

Two of the most widely produced and studied chemicals in the PFAS class are perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS). PFOA and PFOS do not break down and, in fact, can accumulate over time. Because of this, PFAS are also referred to as “forever chemicals.” According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more than 98% of the U.S. population has been exposed to and has measurable concentrations of PFAS in their bodies.

Where are PFAS?

While “PFAS” may be an unfamiliar term, it is likely that you come across these substances on a regular, if not daily, basis. PFAS are found in some nonstick products (think Teflon), food packaging, waterproof fabrics, firefighting foam, mascaras and eyeliners, sunscreens, shampoos, shaving creams, and more. A 2017 study found PFAS in one-third of all fast food wrappers, where the substances can easily seep into greasy foods.

Design by Stuart Cox, Jr. for EARTHJUSTICE

In recent years, PFAS have also been identified in drinking water sources across the United States. Between 2013 and 2015, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) mandated testing for PFAS in public water systems. While those systems with the highest PFAS concentrations were publicly identified, the full results of the testing were never publicized. According to the Environmental Working Group (EWG), public and private water systems in 49 of the 50 United States have tested positive for PFAS contamination.

Why are PFAS in our drinking water? PFAS contaminate our water supplies primarily through industrial discharges and firefighting foams. The danger of contamination is typically localized to specific facilities like those of oil and gas operations, landfills, wastewater treatment plants, military bases, firefighting training sites, and more.

PFAS in Shale Gas Development

Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR) discovered in 2020 that the EPA approved PFAS to be used in more than 1,200 oil and gas wells across six states. The EPA approved the use of these substances in 2011 despite the agency’s concerns about their toxicities.

The use of PFAS in oil and gas operations exposes industry workers and emergency response teams who handle fires and spills, as well as the communities located near or downstream from drilling sites.

There are many ways in which PFAS exposure can occur during oil and gas development, specifically during the phases of drilling, fracking, and disposal. During the drilling of shale gas wells, chemicals are likely to leach into groundwater because they are injected into the ground before the wells are sealed from surrounding aquifers. Once fracking begins, potential exposure pathways include:

fracking fluid spills that seep into groundwater

fracking fluid injections in wells with cracked casings

underground migration of fracking fluids through fracking-related or natural fractures in the bedrock

airborne chemicals from ground-level wastewater pools

During the disposal process, additional exposure pathways include the intentional dumping of fracking wastewater into waterways, the practice of road brining (spreading wastewater onto roads), and the use of wastewater for irrigation.

PFAS and Public Health

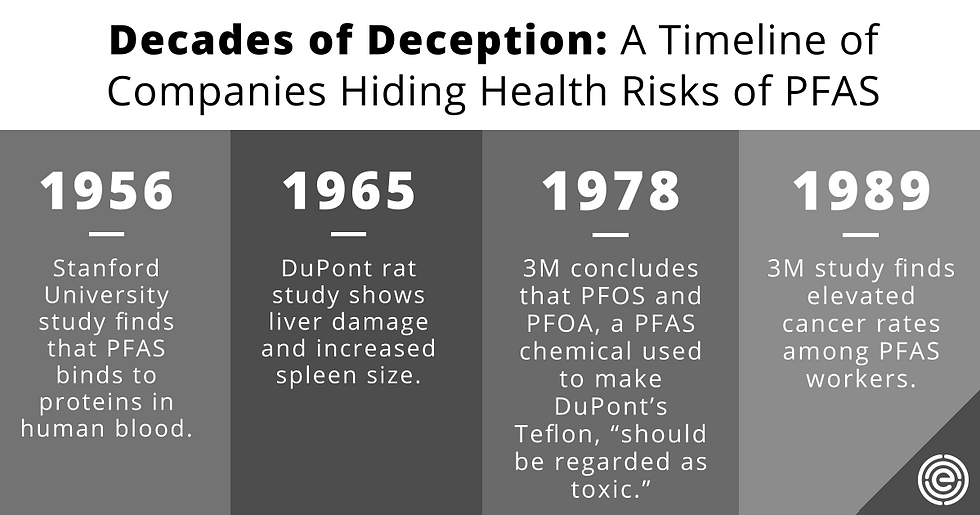

Today, we know that PFAS exposure is a threat to public health. In fact, the dangers of PFAS were discovered nearly fifty years ago, just years after the substances were popularized in the United States.

ewg.org

In the 1970s and 1980s, 3M Company discovered that PFOS and PFOA—chemicals that the company itself had developed—were accumulating within bodies, impacting immune systems, and posing a toxic risk to humans. In 2006, 3M paid more than $1.5 million in penalties to the EPA for 244 violations of the Toxic Substances Control Act. In 2010, the Minnesota attorney general filed a lawsuit against 3M for knowingly polluting groundwater with PFAS. The suit resulted in an $850 million settlement, which Minnesota officials are currently planning to use to remove PFAS from drinking water in local communities.

While the settlement is a win for communities in Minnesota, it points to the alarming scale of PFAS contamination in drinking water and elsewhere across the United States. Though 3M and other producers of PFOS agreed to phase out the chemicals by 2015 due to public health concerns, other PFAS continue to be used across the globe and pose a serious threat to public health. Currently, the EPA has added only 172 of the approximately 4,700 chemicals in the PFAS class to the Toxic Release Inventory. The others remain unregulated at this time.

PFAS have been linked to a wide range of health problems including kidney and testicular cancers, endocrine disruption, increased cholesterol levels, changes in liver enzymes, decreases in infant birth weights, and more. PFAS exposure has also been linked to increased susceptibility to infectious diseases like COVID-19 and reduced effectiveness of vaccines, specifically in children.

Further, measurable levels of PFAS have been found not only in young and adult humans, but also in fetuses. Laboratory tests in 2005 and 2009 found PFOA, PFOS, and other PFAS in the umbilical cord samples from 20 babies born in the United States. Of the 287 chemicals that were detected in these samples, 180 cause cancer in humans or animals, 217 are toxic to the brain and nervous system, and 208 cause birth defects or abnormal development in animal tests.

What You Can Do

To better protect yourself from toxic PFAS exposure:

try to avoid products with non-stick and waterproof properties

eliminate fast food and carry-out packaging

avoid beauty products—makeups, dental floss, shampoos, lotions—that include the term “fluoro” in their ingredients

Taking the time to share your concerns with the companies who produce the products you frequently use, as well as with your local policymakers, can make a difference. While a few companies like IKEA have already begun to eliminate some PFAS from their product lines, those companies are the exception.

Finally, you can urge your representatives to pass legislation that protects your health from PFAS exposure. Demand that state agencies monitor and test for PFAS, conduct health assessments of residents, and provide information about PFAS health risks to the public.

Learn More

The Environmental Health Project (EHP) and Halt the Harm Network (HHN) hosted a webinar on PFAS, Endocrine Disruption, and Shale Gas Development on Tuesday, September 21, 2021, at 7 p.m. View the recording of the webinar here.

Speakers included Dusty Horwitt, J.D., the author of PSR's recently released report Fracking with “Forever Chemicals." Mr. Horwitt discussed the evidence of PFAS within oil and gas operations, the problems with a lack of transparency, and the regulations needed to better protect public health.

In addition, Katherine Pelch, Ph.D., environmental health science and policy analyst and assistant professor at the University of North Texas Health Science Center, discussed the health impacts of PFAS, focusing specifically on endocrine disruption. Dr. Pelch also discussed the PFAS-TOX Database and regulation and exposure mitigation.

The webinar was moderated by Makenzie White, MPH, LSW, Public Health Manager at EHP.

The Environmental Health Project (EHP) and Halt the Harm (HHN) hosted Blair Wylie, M.D., MPH, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard University, and Jamie DeWitt, Ph.D., of East Carolina University, on Tuesday, May 24, 2022. Dr. Wylie discussed the risks of exposure to PFAS substances during pregnancy, and Dr. DeWitt discussed the toxicity and more specifically immunotoxicity of exposure to PFAS substances. The webinar was moderated by Ned Ketyer, M.D., EHP’s Medical Advisor, who began the evening with a brief overview of what is known about the use of PFAS in shale gas development and potential routes of exposure. View the recording of the webinar here.

Comments